As the current Home Secretary is seemingly hell-bent on raising the alarm over migrants crossing the Channel in small boats, and as criticism of the over-statement of her rhetoric is treated as tantamount to treason in certain sections of the press, The Whitworth’s latest exhibition, forging the links between forced displacement and its representation in the visual arts, could hardly be more timely. Under the custodianship of curator Leanne Green, Traces Of Displacement, unlike the amoral certainties of right-justified newspaper headlines, takes the time to tease out the nuances, to make the space for the viewer to think for themselves.

Its prologue is a series of pieces in which the artists speak for the persecuted. Frank Brangwyn, an official war artist during the First World War, casts dark shadows over the subjects of Refugees Leave Antwerp, the blackness of his inks adding depth to the pathetic fallacy of the storm clouds gathering over their heads. Perhaps because he was born in Belgium, the figures in his composition are rendered with a sense of agency less apparent than the ideals he deploys in his later poster for the Spain General Relief Fund. The latter, placing women and children first and foremost, is a plea for sympathy; the former, by contrast, strikes a chord a good deal closer to empathy. This entangling of tropes, the monochrome of misery with the wide eyes of helplessness, is one which continues to be utilised in appeals for charity, hoping to puncture the colour and noise of daytime television, for everything from endangered species to earthquake relief. Effective though it must be, it rarely scratches the surface, showing surprisingly little curiosity as to how things became so black.

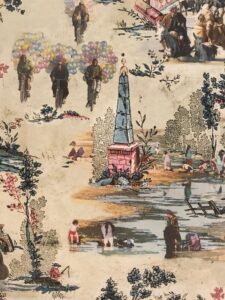

Francesco Simeti, Arabian Nights. Photography by Michael Pollard.

If the opening wave of good intentions speaks on behalf of the persecuted, the pieces which follow direct attention to the displaced who found their artistic voice as refugees from Hitler’s rule by division, a remorseless policy of scapegoating by which the unthinkable inexorably became the done thing. These are works which, on the whole, decline to address the artist’s experience of persecution directly, for all that there’s a pop psychology temptation to read the score of his trauma – his parents were among the millions murdered in Auschwitz – on the tormented body of Frank Auerbach’s Head Of E.O.W.

Even in the long shadow of such horrors, arguably of greatest pertinence is the art which at the last enables the displaced their own place in the conversation, albeit more often than not in conjunction with those whose voices have already been allowed to carry. No Man’s Land, for instance, bears the name of artist Nana Varveropoulou, but the photographic project she has instigated is one in which the images taken from inside Home Office Detention Centres are also ones framed by the detained. The lines of collaboration are defined still more clearly in Alien Citizen, an excerpt from a piece of graphic journalism in which cartoonist Safdar Ahmed, drawing out the cruelties of an Australian Detention Centre, finds a kindred spirit in Kurdish-Iranian heavy metal guitarist, Kazem Kazemi. The love they share for that particular musical territory becomes the language by which they can express their commonality, on equal terms. If other works suggest the retrograde pull of ideologies that trade in dehumanisation, this illuminates a possible path away from its black hole.

Art which deals in certainties risks becoming reduced to the shriek of polemic, encouraging the unconvinced listener to shut up their ears, but equally art which declines to show its times their more unflattering reflection is in peril of becoming nothing more than decoration. By inviting the visitor into the heart of the matter, Traces Of Displacement opens the doors to enlightenment, darkness and all points in-between.

The choice is yours.

Main image: Mounira al Solh, ‘I Strongly Believe in the Right to be Frivolous’, 2012-ongoing, image courtesy of the artist

Traces Of Displacement is at The Whitworth, Manchester until January 7, 2024. For more information, click here.