It is a much-anticipated return, years in the planning. And it’s now less than 12 months until the North East homecoming of the Lindisfarne Gospels.

When the spectacular Gospel book is unveiled in September 2022, it will be the first time that the ancient manuscript has been displayed in Newcastle since 2000, and its first showing in the region since a major exhibition in Durham in 2013. It will be on public display at at Newcastle’s Laing Art Gallery.

The Lindisfarne Gospels will star in an exhibition about its meaning in the world today, exploring its relationship with themes of personal, regional, and national identity. There will also be a variety of public, community and school events across the North East to celebrate the landmark loan from the British Library, as well as a high profile artist commission to reimagine the Gospels for a 21st century audience.

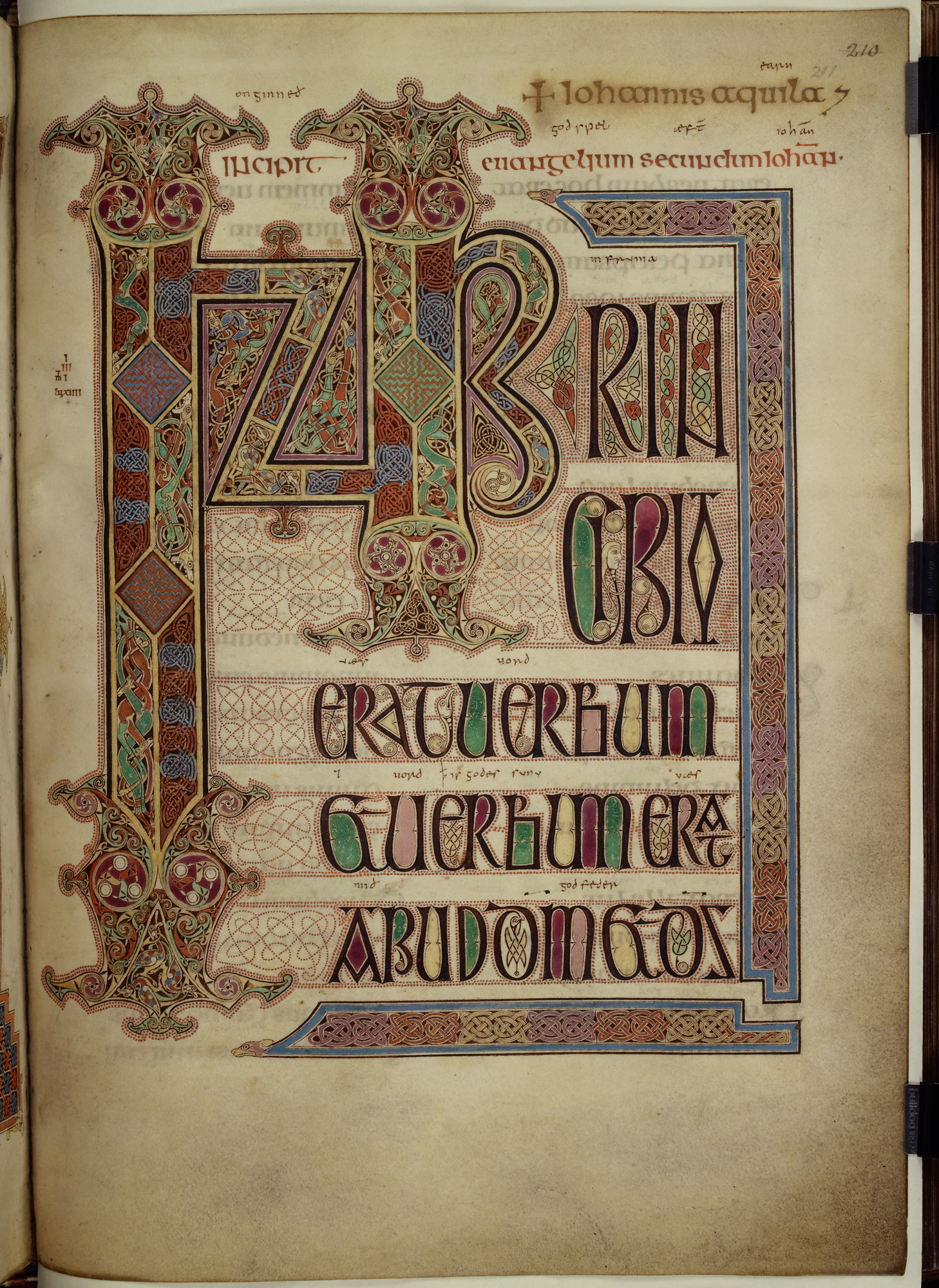

It has also been revealed that the manuscript will be open at the Gospel of John, ff. 210v-211 during its stay in Newcastle. The cross-carpet page and major initial introducing St John’s Gospel are the last major decoration in the manuscript. They demonstrate the different elements of its creator’s decorative vocabulary within a single final tour de force.

It has also been revealed that the manuscript will be open at the Gospel of John, ff. 210v-211 during its stay in Newcastle. The cross-carpet page and major initial introducing St John’s Gospel are the last major decoration in the manuscript. They demonstrate the different elements of its creator’s decorative vocabulary within a single final tour de force.

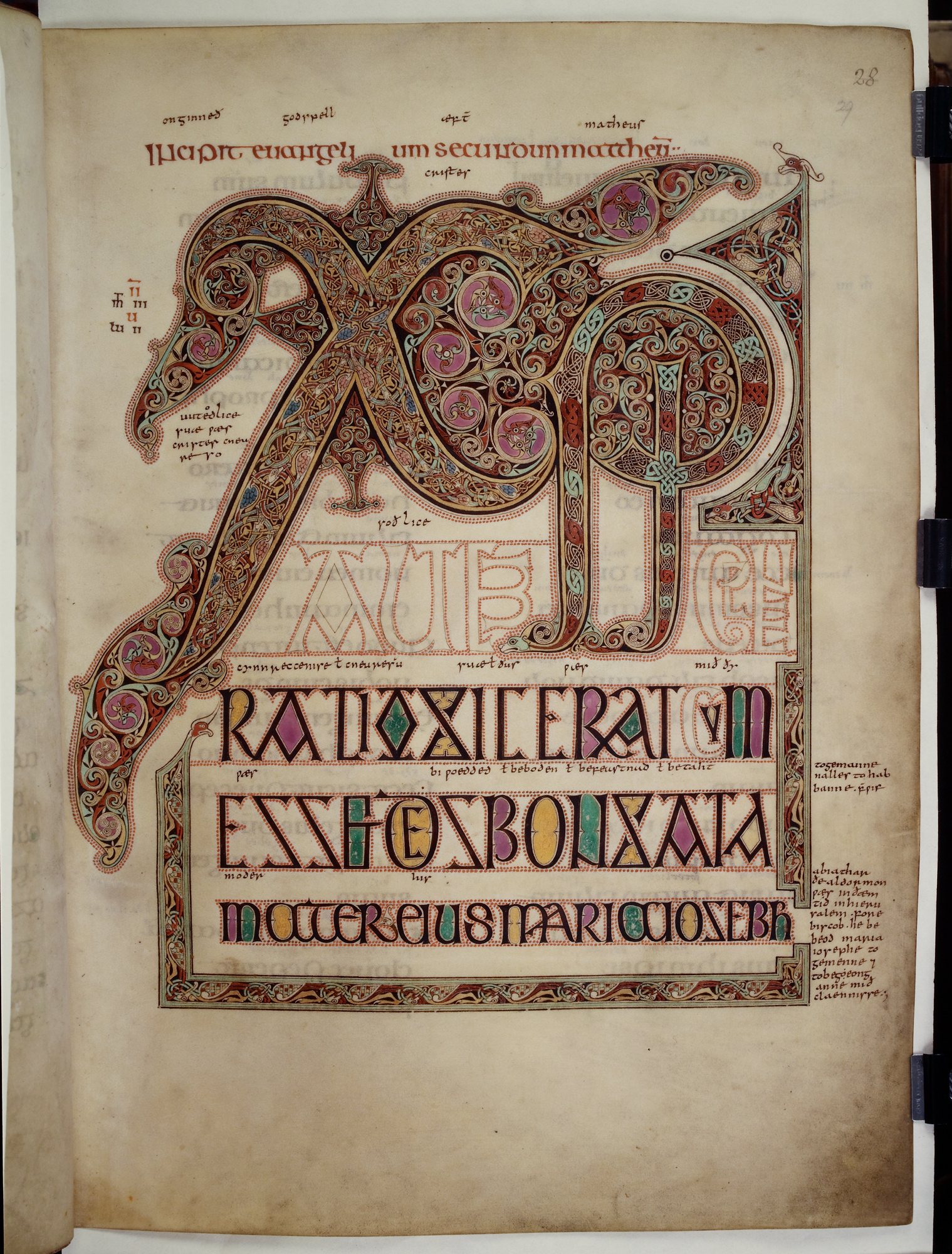

The announcement comes 1,300 years after the death in 721 of the monk named Eadfrith, who became the Bishop of Lindisfarne in 698 and is believed to have created the Gospels in the scriptorium of the monastery on the island. The beautiful, illuminated manuscript was written in Latin and combines Celtic, Germanic, and Mediterranean elements in its decoration. The Lindisfarne Gospels was originally adorned with a metalwork cover or case, reportedly made by Billfrith the Anchorite (a hermit). There is no record of when this cover was separated from the book. The current jewelled, metalwork bookbinding was made for the Gospels in 1853.

What makes the Gospels even more fascinating is the 10th century word-for-word translation of the Latin text into Old English by Aldred, Provost of the monastic community of St Cuthbert at Chester-le-Street. This is the oldest known translation of the Gospels into English. Aldred inserted his text between the lines of Eadfrith’s original around 250 years after the manuscript was first made.

What makes the Gospels even more fascinating is the 10th century word-for-word translation of the Latin text into Old English by Aldred, Provost of the monastic community of St Cuthbert at Chester-le-Street. This is the oldest known translation of the Gospels into English. Aldred inserted his text between the lines of Eadfrith’s original around 250 years after the manuscript was first made.

The four Gospels recount the life and teachings of Christ, according to the Evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. We do not know exactly how the Lindisfarne Gospels was intended to be used in the early Middle Ages. It may have been used for commemoration, sometimes displayed, and occasionally used in major services, but its excellent condition, given its great age, reflects centuries of care and relatively limited handling.

In AD 635, the Irish missionary, Aidan, founded a monastery on ‘a small outcrop of the land’ at Lindisfarne, subsequently also known as Holy Island. St Cuthbert, Bishop of Lindisfarne, died in 687, and a pilgrimage centre dedicated to him developed in the following years. The veneration of the saint’s shrine inspired increasing numbers of pilgrims to travel to the island.

In AD 635, the Irish missionary, Aidan, founded a monastery on ‘a small outcrop of the land’ at Lindisfarne, subsequently also known as Holy Island. St Cuthbert, Bishop of Lindisfarne, died in 687, and a pilgrimage centre dedicated to him developed in the following years. The veneration of the saint’s shrine inspired increasing numbers of pilgrims to travel to the island.

It is believed that it may have taken between five and ten years to create the 518-page Gospel book. It was written on parchment made from calfskin and decorated using a relatively restricted number of pigments, made from a variety of vegetable and mineral sources, which were skilfully combined to create a wide palette of colours. A tiny amount of gold was also used in the decoration.

As a consequence of Viking raids, the monastic community left Lindisfarne around 875, taking Cuthbert’s relics with them. The community eventually settled at Chester-le-Street in 883, where it remained until 995 when further Danish raids prompted it to move first to Ripon and then finally to Durham.

As a consequence of Viking raids, the monastic community left Lindisfarne around 875, taking Cuthbert’s relics with them. The community eventually settled at Chester-le-Street in 883, where it remained until 995 when further Danish raids prompted it to move first to Ripon and then finally to Durham.

It is likely that the Lindisfarne Gospels was taken to Durham from Chester-le-Street. Historical records document the existence of various Gospel books at Durham in the Middle Ages, and the Lindisfarne Gospels may be one of those listed, but it is impossible to be certain. The next conclusive evidence of the location of the Gospels after the 10th century is not until 1605 when an inscription records that they were in the possession of Robert Bowyer, clerk of the parliaments and keeper of the records in the Tower of London. The Gospels subsequently came into the possession of Sir Robert Cotton (1571–1631) whose heir gave his library to the nation in 1702. It became a founding collection of the British Museum in 1753 and was transferred to the British Library upon its creation in 1973.

Working with the British Library and various artists, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums art curators will explore how the book can bring people together today by inspiring thinking about who we are and where we come from, around identity, creativity, learning and sense of place.

Working with the British Library and various artists, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums art curators will explore how the book can bring people together today by inspiring thinking about who we are and where we come from, around identity, creativity, learning and sense of place.

Main image: Front cover of Lindisfarne Gospels c. 700 (Cotton MS Nero D IV) (c) British Library Board.

To find out more, visit laingartgallery.org.uk.

Click here to view our photo gallery of the Lindisfarne Gospels.