Sleet has ushered an audience layered to face its petulant chill into the blackened stone of Chetham’s Library’s 15th century Baronial Hall in Manchester. Beneath its exposed beams, joined at their apex like hands coming together in prayer, they bustle and jostle into pews of velveteen chairs. Anything but hushed, their polite expectation is more akin to the queues forming for a recording of Antiques Roadshow than a lecture on 18th century engraving, albeit one spiced with tales of scandal and disease.

The congregants, as it turns out, are in capable hands. From behind her pulpit, Dr Noelle Dückmann-Gallagher, author of the invitingly-titled Itch, Clap, Pox: Venereal Disease in the Eighteenth Century Imagination, presides over her audience with the wit that comes from having her subject at her command.

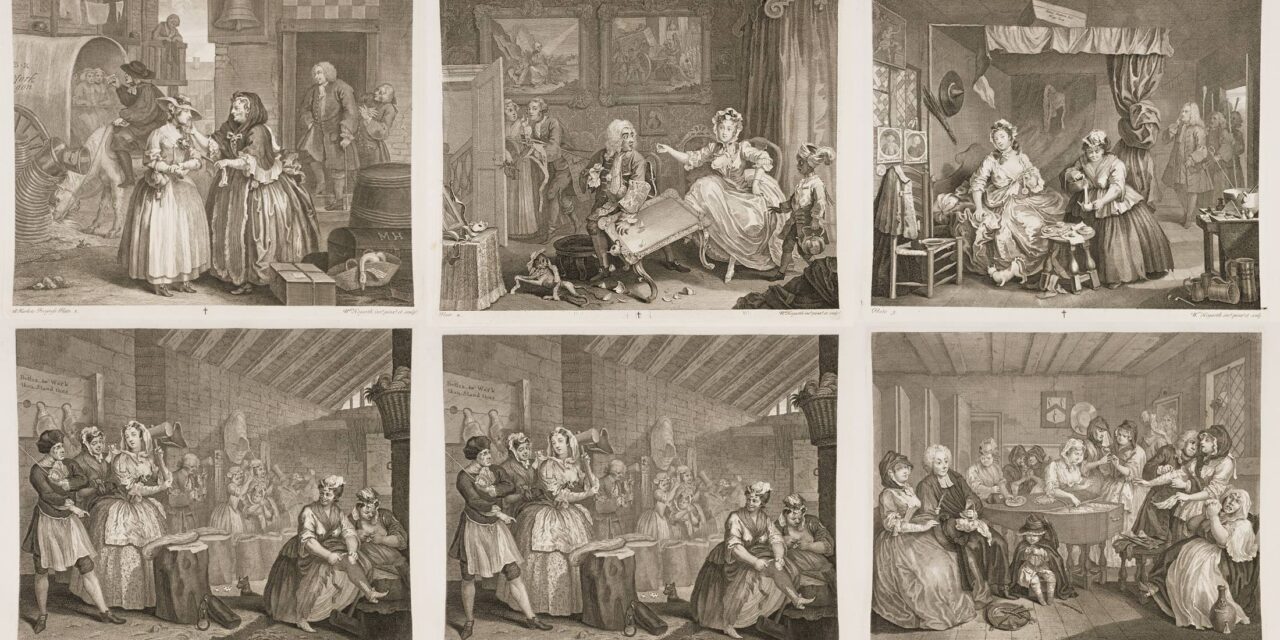

Of course, it’s hardly a hindrance that the tale she has to tell requires little in the way of lubrication. The pretext for her talk, a disquisition on the narrative ambiguities key to captivating the viewer of William Hogarth’s A Harlot’s Progress, is the rediscovery of an edition of those very engravings by a work experience student at Chetham’s, recognising them for what they were, though abandoned between the unprepossessing covers of a scrapbook.

Dückmann-Gallagher ably sets the scene, placing Hogarth in the context of the media of his day. Selling his first editions by subscription, subsequent print runs were considerably more affordable, allowing them to circulate widely beyond the upper class patrons of art with whom Hogarth had in any case a decidedly ambivalent relationship. Supplementing these official publications, Hogarth’s popularity was further enhanced through being paid the financially inconvenient compliment of going on to be pirated. A good two centuries before Warhol and his kin, this was pop art. More than that, though, in its often critical inclusion of recognisable public figures, it was popular art that approximated the editorial cartoons still extant in newspapers today.

Dückmann-Gallagher ably sets the scene, placing Hogarth in the context of the media of his day. Selling his first editions by subscription, subsequent print runs were considerably more affordable, allowing them to circulate widely beyond the upper class patrons of art with whom Hogarth had in any case a decidedly ambivalent relationship. Supplementing these official publications, Hogarth’s popularity was further enhanced through being paid the financially inconvenient compliment of going on to be pirated. A good two centuries before Warhol and his kin, this was pop art. More than that, though, in its often critical inclusion of recognisable public figures, it was popular art that approximated the editorial cartoons still extant in newspapers today.

The first of what he termed his Modern Moral Subjects, The Harlot’s Progress, sits somewhere between a secular Stations Of The Cross and a comic strip as it plots the rise and fall of one Moll Hackabout, a Yorkshire lass lured to London by its promises of betterment. There are parallels, albeit from a more male-directed gaze, with Michel Faber’s richly-imagined novel, The Crimson Petal And The White in the complexities of perspective with which Hogarth is able to imbue each of his six panels.

Like Faber’s protagonist, Sugar, Moll’s capacity for agency is continually curtailed by her circumstances, as limiting as the prints’ panel borders. To begin with, for example, she is greeted in Cheapside, not only by the notorious madam, Elizabeth Needham, but also serial predator, Francis Chateris, convicted of – and subsequently pardoned for – the rape of a servant. While such details seem designed to evoke anger at the outrageous abuse of the privilege wealth and status convey (plus ça change), others are more clearly comedic in intent. In the second pictorial chapter of her story, Moll creates a diversion, enabling her romantic lover, making the ‘small penis’ gesture, to be ushered away from the notice of the wealthy merchant who is keeping her in pet monkeys and West Indian servant boys. It could be a scene from one of the Confessions films of British sexual comedies from the 1970s.

Hogarth goes on to fill out his illustrated narrative with side-swipes, decades before Wilde’s first-hand The Ballad of Reading Gaol, at the dehumanising effect of prison conditions, as well as the quackery of ineffective ‘cures’ for venereal disease peddled by the likes of medical professionals such as Richard Rock and Jean Misaubin, before Moll’s premature passing at the age of 23.

All in all, it’s as fine a way as any to dip one’s toes into the waters of Chetham’s archive, as well as an introduction to an author who is engaging in her own right, bringing a spotlight to bear on the space cleared for erudition between art, literature and social history. Future evenings in a similar vein would be well worth subjecting oneself to the vagaries of the Manchester climate.

Images courtesy of Chetham’s Library

For more information about Chetham’s Library, click here.