It’s not paper alone that is bound by the practice of bookmaking but time itself, compressed by the artistry and labour of both printer and scribe into something light and tangible enough to be held in one’s hand.

This fittingly compact exhibition at Treasures of the Brotherton Gallery in Leeds, made up of barely a baker’s dozen of artefacts, is heavy with the weight not only of more than a millennium of human experience, but, in many cases, the time it took to illuminate them with an exacting hand.

Gathered under glass, they comprise a selection of Leeds University Library’s acquisitions from Arts Council England’s Acceptance in Lieu programme, a means by which inheritance tax can be paid through the transfer of objects of cultural significance from the deceased’s estate to that of the nation. Originating in the collection of Thomas Edward Watson, who made his profits from shipping and coal, they are complemented by volumes that once belonged to the gallery’s own benefactor, the industrialist Edward Allen Brotherton. Intriguingly, the two men frequented the same antiquarian book dealer in London, but, if there was any rivalry in life, time’s passage has made them posthumous collaborators. Between them, the pick of their collections bear testament to the life cycle of the library; from revered treasures to scrap material, and – if only occasionally – back again.

Ornamented initial letter from Sir Thomas Watson’s copy of Hoccleve’s Regiment of Princes, c.1420. Credit: Leeds University Library.

The former quality is perhaps best exemplified by the extraordinary books of devotion which open the display, produced by hand before the invention of the printing press; bibles and missals which informed worship in a time when the existence of God was accepted as a gospel truth, or at least one not to be publicly questioned, and, in the painstaking patience their reproduction must have necessitated, acted as manifest signs of such faith in themselves.

These were articles that the owner must have handled with all the attentive care due to what would have taken to be the word of God, and the worn pages of the oldest exhibit, a Greek gospel book from the turn of the last millennium, attest to its frequent contemplation. Beyond study or recitation, however, these were also objects that were physically engaged with, as a 15th century reader’s rendering of St Matthew, too precise for idle graffiti, making use of the devotional space suggested by a blank leaf in its frontispiece, rather delightfully testifies.

While the chapter and verse of the Bible must have been regarded as inviolable, and fidelity to them sacrosanct, other texts were riper for embroidery with each retelling. The Brut Chronicle, a history written originally in French, merrily conflated the factual and the fictional in its fanciful chronology of the British Isles. Although such an approach compromises its documentary authenticity, its intrinsic mutability afforded leeway for the addition of newer material at every transcription. So it is, for example, that one version incorporates a near-contemporaneous account of the Peasant’s Revolt of 1381, as though hot-off-the-presses that had yet to be invented.

If these texts have survived largely unscathed, other exhibits have been less well treated. A copy of poet Thomas Hoccleve’s The Regiment Of Princes has suffered the indignity of mutilation, its pages butchered of its illuminated letters in the fad for decoupage, in a particularly cruel affront to the esteem in which its poetry must have been held by the scalpel wielder in question.

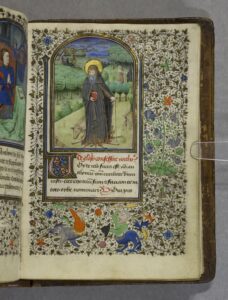

Page from the Hours of Antoine de Crèvecœur, 15th century, collected by Lord Brotherton. Credit: Leeds University Library.

If one takes the time to read between the lines, what Books and Benefactors has to offer is binding. Prepare yourself to be spellbound.

Main image: Double page from Lyriques choisis de poètes français, calligraphed by Alberto Sangorski, Special Collections. Image credit: Leeds University Library.

Books and Benefactors is at Treasures of the Brotherton Gallery until April 6, 2024. For more information, click here.